Bernd W. Krysmanski, "Joachim Möller, ed. Hogarth in Context: Ten Essays and a Bibliography (Marburg: Jonas Verlag, 1996); Peter Wagner, Reading Iconotexts: From Swift to the French Revolution (London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 1995)", Eighteenth-Century Studies, 33, no. 1 (Fall 1999), 139-41. [Book reviews.]

Bernd W. Krysmanski, "Introduction: A Brief Account of Hogarth's Life and Work", in Bernd W. Krysmanski (ed.), Hogarth: 50 New Essays: International Perspectives on Eighteenth-Century English Art (forthcoming).

Bernd W. Krysmanski, "The Paedophilic Husband: Why the Marriage A-la-Mode Failed", in Bernd W. Krysmanski (ed.), Hogarth: 50 New Essays: International Perspectives on Eighteenth-Century English Art (forthcoming).

Bernd W. Krysmanski, "Hogarth's Gate of Calais: An Expression of Anti-French Nationalism", in Bernd W. Krysmanski (ed.), Hogarth: 50 New Essays: International Perspectives on Eighteenth-Century English Art (forthcoming).

Bernd W. Krysmanski, "Hogarth and Dürer: A Case of Rejection and Hidden, Ironic Borrowing", in Bernd W. Krysmanski (ed.), Hogarth: 50 New Essays: International Perspectives on Eighteenth-Century English Art (forthcoming).

Bernd W. Krysmanski, "Hogarth's Unknown Caricature of Johnson", in Bernd W. Krysmanski (ed.), Hogarth: 50 New Essays: International Perspectives on Eighteenth-Century English Art (forthcoming).

Bernd W. Krysmanski, A Hogarth Bibliography: An Annotated Index on the Source Literature of William Hogarth and his Works, Collated as an Interdisciplinary Research Tool, 2 vols. (forthcoming).

Bernd Krysmanski, Hogarth's Enthusiasm Delineated: Nachahmung als Kritik am Kennertum. Eine Werkanalyse. Zugleich ein Einblick in das sarkastisch-aufgeklärte Denken eines "Künstlerrebellen" im englischen 18. Jahrhundert.

English title: Hogarth's Enthusiasm Delineated: Borrowing from the Old Masters as a Weapon in the War between an English Artist and self-styled Connoisseurs. A detailed study in iconology against a background of religion, society and culture in mid-eighteenth-century England. Based primarily on primary sources.

2 volumes, Hildesheim, Zurich, New York: Georg Olms, 1996.ISBN: 3-487-10233-1 and 3-487-10234-X.

Volume 1: main text. Volume 2: summary for English readers, appendix including quotations from contemporary sources, bibliography and index. XVII/1469 pages. 446 illustrations.

Enlarged and slightly revised version of the author's PhD thesis of 1994, now containing, in volume 2, apart from the contemporary sources and the 446 illustrations, a summary for English readers and a comprehensive index. See also the German abstract by the author and the English review by Thomas Krämer, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 33, no. 1 (1999), 143-45.

ABSTRACT

William Hogarth's Enthusiasm Delineated (1761) is an artist's manifesto which could well be renamed "Hogarth Delineated". Its imagery, borrowed - ironically - from "high" art (e.g. from works by Raphael, Dürer, Michelangelo, Correggio, Rubens, Rembrandt or Charles Le Brun), provides the key to a new understanding of the purpose behind Hogarth's taking single motifs from the works of highly reputed Old Masters and using them in new, topical, but often "low" contexts. The author's interdisciplinary study interprets this borrowing method as a cleverly contrived "anti-iconography" with which Hogarth ridicules the English self-styled connoisseurs of his time. A novelty in Hogarth research, the study also contains a thorough formal analysis of the print.

In addition to Enthusiasm Delineated, numerous other Hogarth works are reassessed in detail. A seventy-page excursus deals with the pulpiteer as an artistic motif through the ages. The text includes a great number of original quotations from contemporary periodicals, pamphlets and treatises, concerning the theory of art (eclecticism, picture auctions, criticism of connoisseurship, the profane and blasphemy in art), the history of religion and religious tradition (English Puritanism, deism, Methodism [particularly George Whitefield], antipapism, witchcraft and demonology, iconoclasm, anti-Semitism, antitrinitarianism, the debate on transubstantiation), as well as social, cultural and medical history (the anatomy of the brain, the maltreatment of dogs, physiognomy, eroticism, sex murder, eighteenth-century melancholy, madness, and enthusiasm). Some of these sources are reprinted for the first time and may be of interest not only to art historians, but also to theologians, members of the Methodist Church, general historians, philologists or other scholars working on eighteenth-century England.

Although the book focuses on Enthusiasm Delineated, it invariably leads to new readings of the numerous other works by Hogarth. Literature on Methodism (rather than on Hogarth), for example, allows the preacher sitting next to Tom Idle in the prisoner's cart in Industry and Idleness, Pl. 11 (1747) to be identified as Silas Told (1711-1778). The same print, as a whole, may allude to traditional depictions of a Massacre of the Innocents. The study also shows the extent to which Hogarth's Sigismunda (1759) was influenced by the English Melancholy portrait tradition. A woodcut in Johannes de Ketham's Fasciculo di medicina (1493), depicting an anatomical lesson by Mondino de'Luzzi, can be identified as a direct model for The Reward of Cruelty (Pl. 4 of Hogarth's series The Four Stages of Cruelty; 1751). Fra Angelico's St. Stephen preaching and the Dispute before the Council (1447/50; Vatican, Cappella di Niccolo V) seems to be the model for both Paul before Felix (1748) and Paul before Felix Burlesqued (1751). Hogarth's early print, Masquerades and Operas (1724) has borrowed some motifs from a woodcut by Urs Graf (?) in Hans Heinrich Freiermut's Triumphus veritatis (1524). Hudibras catechized from Hogarth's Twelve Large Illustrations for Samuel Butler's 'Hudibras' (1726) may be a play on Lucas Cranach's Martyrdom of St. Jude Thaddaeus (c. 1512) or Poussin's Massacre of the Innocents (1628/30; Chantilly, Musée Condé). Cruelty in Perfection (1751) probably alludes to Anthony van Dyck's Capture of Christ (c. 1621; Madrid, Prado; repetition, c. 1629, Corsham Court, Bristol Museum and Art Gallery). Chairing the Members from Hogarth's Election series (c. 1754; Sir John Soane's Museum, London) may allude to some details in Raphael's Expulsion of Heliodorus (c. 1512; Stanza d'Eliodoro, Vatican). Dürer's Young Woman attacked by Death (Der Gewalttätige; c. 1494) is the model for Before (1736). Chapter 4.8.3 includes detailed comments on the iconographic backgound of the Harlot and the Rake series.

It should be noted that the study also touches upon a number of other aspects of Hogarth's art. Chapter 4.10.7 looks at dogs in Hogarth's oeuvre, and particularly at the howling Irish Setter in Enthusiasm Delineated. Chapter 4.10.8 explores the Sacrifice of Isaac theme in Hogarth's art, and chapter 6.5 Hogarth's church interiors. It is proposed, for example, that Plate 2 of Industry and Idleness (1747) depicts the interior of St. Peter's, Vere Street (formerly Marybone Chapel), and not of St. Martin-in-the-Fields whose box pews were not introduced into the body of the church until 1799. Apart from questions of content, the book also contains detailed formal analyses of Hogarth's art. Chapter 4.8.4 is about how Hogarth quite deliberately employed his "Line of Beauty (and Grace)" in several of his paintings. General remarks on the formal structure of Hogarth's paintings and engravings can be found in chapter 7. The use of linear perspective is touched upon here, as well as Hogarth's understanding of light and shadow. This chapter also goes into Hogarth's ironic use of the triangle motif.

All in all, the book is a social and cultural history of mid-eighteenth-century London rather than a monograph on a single Hogarth print.

ENGLISH TABLE OF CONTENTS

Volume One

PRELIMINARY NOTES 1

1. FACING THE PROBLEM 22

- 1.1. A Preacher Mocked 22

- 1.2. "A Timeless Print?" 23

- 1.3. The First Impression 24

- 1.4. The Grotesque in Enthusiasm Delineated 26

- 1.5. Hogarth's "Advertisement": A First Glance at the Artist's View 29

2. THE ANGLICAN CHURCH FROM HOGARTH'S POINT OF VIEW 30

- 2.1. Hogarth and the English Clergy 30

- 2.2. Excursion 1: The Eighteenth-Century Anglican Church 34

- 2.3. The Sleeping Congregation 42

3. THE PRINT'S FIRST LAYER OF MEANING: RELIGIOUS FANATICISM MOCKED 60

- 3.1. The Minister as Enthusiast 60

- 3.2. Excursion 2: George Whitefield and the Methodists 62

- 3.3. Enthusiasm Delineated: An Anti-Methodist Satire 83

- 3.3.1. Is that Whitefield in the Print? 83

- 3.3.2. The Preacher as a Fool 86

- 3.3.3. The World turned into Hell 93

- 3.3.4. The Meeting-Place: A Madhouse, a Prison or a "Tabernacle" Scene?104

- 3.3.5. The Lustful Congregation 120

- 3.3.6. The Nobleman and Whitefield 144

- 3.3.7. The Preacher as a Disguised Jesuit 149

- 3.3.8. The "Poor's Box": just a Mousetrap 154

- 3.3.9. Hogarth's Early Views on Methodism 158

- 3.3.10. "Humbly Dedicated to His Grace the Archbishop of Canterbury" 161

- 3.3.11. "A Methodist's Brain" 167

- 3.3.12. A Mohammedan as Observer 176

- 3.4. Short Summary 185

- 3.5. The Point of View has Slightly Changed: Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism 187

- 3.6. A Question Thrown In 219

4. THE HIDDEN MEANING OF THE PRINT: A CUTTING PARODY OF HIGH RELIGIOUS ART 222

- 4.1. Anti-Christian Motifs 222

- 4.2. Hogarth as Opponent of Sacred Art? 227

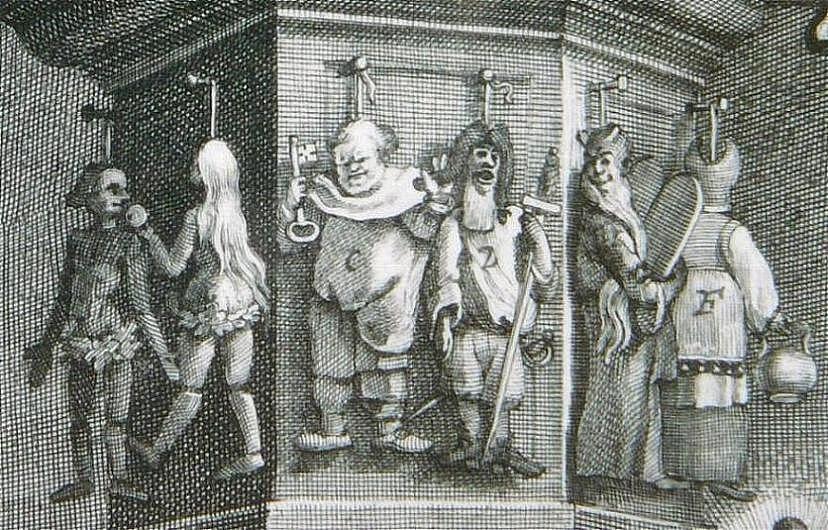

- 4.3. Hogarth versus the Old Masters: The Puppets of the Clergyman 231

- 4.3.1. God no longer the Almighty? 233

- 4.3.2. The Devil as the True Ruler of the World 237

- 4.3.3. Peter 242

- 4.3.4. Paul 244

- 4.3.5. Adam and Eve 246

- 4.3.6. Moses 252

- 4.3.7. Aaron 258

- 4.3.8. The Meaning of the Puppets 260

- 4.3.8.1. A Satire on Puppet-Shows of Old? 260

- 4.3.8.2. A Play on Baroque Pulpit Ornaments? 263

- 4.4. Excursion 3: The Eclectic Theory of Art 268

- 4.4.1. The Origin of the Eclectic Theory in Italy 269

- 4.4.2. The Movement of the Theories of "Imitation" from Italy to France 271

- 4.4.3. Eclecticism in Eighteenth-Century England 275

- 4.5. Eclecticism from Hogarth's Point of View: Borrowing from the Old Masters as an English artist's weapon against the false and antiquated doctrines of self-styled connoisseurs 286

- 4.6. Contemporary Public Opposition to Connoisseurs and Art Dealers 302

- 4.6.1. Essays and Plays in 1761 302

- 4.6.2. A Satire on Picture Auctions: The Real but Disguised Meaning of the Print 319

- 4.7. The Burlesque Tendency in Hogarth's Art 329

- 4.7.1. Reynolds's Idler: Forbidden Mixture of the High and Low in Art! 329

- 4.7.2. Hogarth's England and Dutch Art 333

- 4.7.3. The Dutch or "Vulgar" Element in Hogarth's Art 338

- 4.7.4. The "Test of Ridicule" 347

- 4.8. The Critics' Action and the Artist's Re-Action: Hogarth's Failure in High Art and his Revenge 352

- 4.8.1. Hogarth's Turn Away from the "Sublime": the Creation of his "Modern Moral Subjects" 352

- 4.8.2. Hogarth's Ploy: Borrowing from the Old Masters to Exalt Low Art? 361

- 4.8.3. Some Examples of Hogarth's Borrowing from the "Sublime" 364

- 4.8.4. Hogarth's "Anti-Iconography" as a Method of Exposing "Connoisseurs" 387

- 4.9. Excursion 4: English Iconoclastic Tradition 411

- 4.9.1. Three Principal Reformers from the Continent 414

- 4.9.2. Iconoclasm in Pre-Reformation England 417

- 4.9.3. The Iconoclastic Attitude of English Reformers 422

- 4.9.4. The Roman Catholic Reaction at the Council of Trent 428

- 4.9.5. Puritan Radicalism and the Oppression of Archbishop Laud's Conservatism 430

- 4.9.6. After the Restoration 438

- 4.9.7. The Question of "Images" in Hogarth's England 445

- 4.9.7.1. "Grand Tourists" and Continental Idolatry 445

- 4.9.7.2. Anglican Churchmen as Advocates of Pictures 449

- 4.9.7.3. The Opinion of British Artists, Critics, and Connoisseurs 452

- 4.9.7.4. The Pros and Cons of Representing God as an Old Man 464

- 4.9.7.5. Contemporary Discussion of Religious Art: The Ornaments of Churches Considered (1761) 470

- 4.10. Enthusiasm Delineated: The Motifs Parodied in the Lower Half of the Print 476

- 4.10.1. The Cherubim 477

- 4.10.2. The "Fallen Lady" 484

- 4.10.3. The Cowering Dark Woman Sitting in the Shade of the Clerk's Lectern 517

- 4.10.4. The Turk and the "Blessed Virgin" 531

- 4.10.5. The Jew 539

- 4.10.6. The "Mob" in the Back Pews 553

- 4.10.7. The Dog 561

- 4.10.8. Abraham's Sacrifice of Isaac 575

- 4.10.9. Enthusiasm Delineated as an Anti-Eucharistic Demonstration 586

- 4.10.10. The Holy Spirit appearing in a Murderer's Brain 615

- 4.10.11. The Weeping Criminal: A Portrait of the Artist Theodore Gardelle 620

- 4.10.12. The Holy Ghost as a "mighty rushing Wind" 636

- 4.10.13. A Paradox: Sex, Crime and Protestant Religious Art 643

- 4.10.14. Enthusiasm Delineated as an Antitrinitarian, Polytheistic Work of Art 655

- 4.11. Short Summary 673

- 4.12. Who is the Clerk? 676

5. "ENTHUSIASM" AS "LEITMOTIF" 688

- 5.1. Eighteenth-Century "Enthusiasms" 688

- 5.2. The "Mental Thermometer" - A Scale of "Enthusiasm"? 708

- 5.3. Fine Arts Enthusiasm 728

- 5.4. A Call for Pulpit Enthusiasts 743

6. THE PULPITEER AS MOTIF IN ART: AN ICONOGRAPHIC SURVEY 755

- 6.1. Preacher-Motifs from Earliest Times to the End of Early Renaissance Art 755

- 6.2. Sixteenth-Century Preachers in anti-papist, didactic, genre and satirical Contexts 767

- 6.3. The Image of the Preacher in Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth-Century Art: Mainly Ecstatic? 783

- 6.4. Preachers in Eighteenth-Century English (and French) Art 800

- 6.5. Hogarth's Views of Church Interiors 805

- 6.6. Satires on Orator John Henley as Models for Hogarth's Preacher? 812

- 6.7. Short Summary 823

7. FORMAL ANALYSIS 825

- 7.1. The Pictorial Space 825

- 7.2. Brute, compulsive Vulgarity amidst angular Austerity 831

- 7.3. A Piercing Light: Hogarth's Playful Juxtaposition of Classical and Baroque Devices 840

- 7.4. The Total Negation of Classical Composition 853

- 7.5. Roger de Piles' Balance as Puppet-Show 873

- 7.6. Short Summary 877

8. CONCLUSION 879

Volume Two

9. SUMMARY FOR ENGLISH READERS 895

10. APPENDIX 905

- 10.1. Contemporary Sources 907

- 10.1.1. "Of Connoisseurs in Painting" 907

- 10.1.2. "Of Connoisseurs in Painting, Letter II" 912

- 10.1.3. "On the Exhibition of the Artists" 916

- 10.1.4. "Projected Exhibition of the Sign Painters" 919

- 10.1.5. The Life of Theodore Gardelle, Limner and Enameller 921

- 10.2. Bibliography 933

- 10.3. List of Illustrations 1011

- 10.4. Illustrations 1026

- 10.5. Index 1241-1469

|

SHORT ABSTRACTS OF THE AUTHOR'S PUBLISHED ARTICLES ON WILLIAM HOGARTH

Bernd Krysmanski, "Hagarty, not Hogarth? The True Defender of English 'Wit and Humour'", in The Dumb show: Image and society in the works of William Hogarth, ed. Frédéric Ogée, Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1997 [Studies on Voltaire and the Eighteenth Century, 357], 141-59.

This essay proposes the hypothesis that the Irish artist James Hagarty (fl. 1762-1783), not Hogarth, was the leading artistic force behind Bonnell Thornton's parodic Sign Painters' Exhibition of 1762, and that Hogarth's involvements in court art and his turning away from "modern moral subjects" at the end of his life seems to have been one of the targets of the satirical exhibits presented at that show.

* * *

Bernd Krysmanski, "'O the Roast Beef of Old England': Hogarth in BSEfreier Zeit vor dem Tor von Calais", Lichtenberg-Jahrbuch 1997 [Saarbrücken: SDV, 1998], 29-52, 115, 178, 195, 217.

This is an extended version of a paper first read on 6 July, 1997 at the twentieth annual meeting of the Lichtenberg-Gesellschaft in Ober-Ramstadt (the birthplace of the famous German Hogarth commentator Georg Christoph Lichtenberg) on the occasion of Hogarth's tercentenary. It explains the nationalist implications of the English taste for roast beef and the Francophobe and antipapist sideswipes and puns in Hogarth's The Gate of Calais. The paper compares, in addition, the gate as shown in the picture with a traditional Gate of Hell and the contrasting motifs of a fat monk and meager French soldiers with Bosch's Gula and Bruegel's Poor and Rich Kitchen. It also includes a brief discussion of Steve Bell's political caricature of 1996 after Hogarth's print.

* * *

Bernd Krysmanski, "Patriotisches Rindfleisch, Pariser Pantinen und eine jakobitische Krähe: Ein auf Erkenntnissen von Katharina Braum fußender Nachtrag zu Hogarths 'Gate of Calais' nebst einer ergänzenden Hypothese von Elizabeth Einberg", Lichtenberg-Jahrbuch 1998 [Saarbrücken: SDV, 1999], 286-92.

Additional remarks on the foregoing essay, focusing on the Francophobe motif of wooden shoes and the crow sitting on the cross of the gate in Hogarth's painting of The Gate of Calais, and including a hitherto unpublished hypothesis by Elizabeth Einberg on the motif of the crow.

* * *

Bernd Krysmanski, "Hogarth's A Rake's Progress: An 'Anti-Passion' in Disguise", 1650-1850: Ideas, Aesthetics, and Inquiries in the Early Modern Era, 4 (1998), 137-82.

This is an enlarged version of a paper first delivered in September, 1993 at the Paul MellonCentre for Studies in British Art, London, on the occasion of a colloquium on English eighteenth and nineteenth-century art in recent German scholarship. The essay interprets the eight-picture Rake's Progress series as an allusion to the life of Christ. According to this reading, the first scene is the Raising of the Cross; the second the Flagellation; followed in Plate 3 by the Washing of the Feet at a rather "obscene" Last Supper. Scene 4 alludes to Hans Holbein's Noli me tangere and to the Soldiers drawing Lots for Jesus' Cloak; Plate 5 to a Florentine Marriage of the Virgin; followed in Plate 6 by a parody of Raphael's Transfiguration. The seventh scene may play on either the Repose of Christ or Christ's Imprisonment, with some details perhaps borrowed from a Temptation of St Antony or a Harrowing of Hell. The pictorial drama closes with the Lamentation of Scene 8.

* * *

Bernd Krysmanski, "Hogarth's 'A Rake's Progress' als 'Anti-Passion' Christi (Teil 1)", Lichtenberg-Jahrbuch 1998 [Saarbrücken: SDV, 1999], 204-42; and "Hogarths 'A Rake's Progress' als 'Anti-Passion' Christi: Ein Erklärungsversuch (Teil 2)", Lichtenberg-Jahrbuch 1999 [Saarbrücken: SDV, 2000], 113-60.

An extended and reorganized German version of the foregoing English essay, now published in two parts. Includes additional material in order to support the view that the whole Rake series alludes to the life of Christ. The second part evaluates in detail Hogarth's blasphemous tendency to profane traditional subjects of Christian iconography in his works, thereby interpreting this negative secularisation as deistic satire tinged with black humour, and as a "test of ridicule" aimed at the self-styled English connoisseurs.

* * *

Bernd Krysmanski, "We see a Ghost: Hogarth's Satire on Methodists and Connoisseurs", Art Bulletin

, 80 (June 1998), 292-310.

This paper compares the Hogarth print, Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism (1762)

with its rather different, unpublished first state,