HOGARTH'S ELECTION SERIES

William Hogarth (1697-1764)

AN ELECTION

A series of four

Ink Etchings

Oil paintings

An Election Entertainment.

Canvassing for Votes.

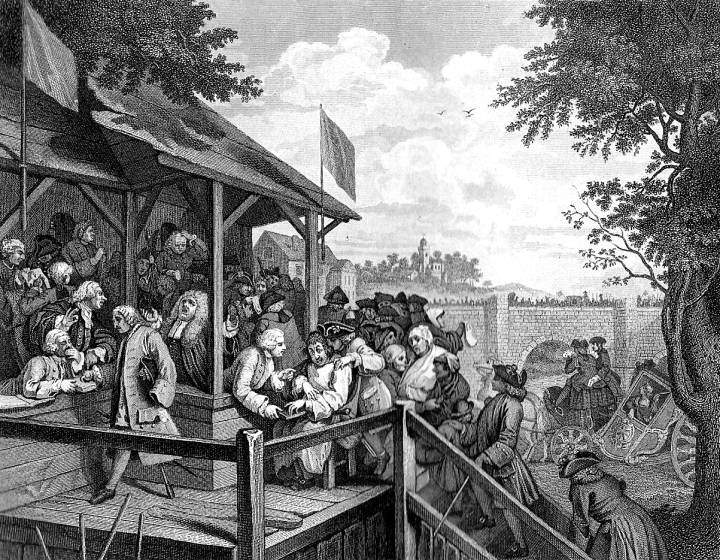

The Polling.

Chairing the member.

From the art collection of SIR JOHN SOANE'S MUSEUM,

13 Lincoln's Inn Fields, London, WC2A.

We complain about partisanship and negative campaigning, but compared with these scenes - a little exaggerated, to be sure - our elections are but quilting bees. What say you, are we more civilized or do we no longer have the stomach for real politics?

For his last and grandest series, An Election, Hogarth took on the state of the nation. His inspiration was the spectacularly corrupt Oxfordshire election of 1754, but his subject was the old wives' tale that Britain was ruled by virtuous property owners who gathered together to deliberate on public affairs. Executed on a scale usually reserved for elevated history painting, the canvases were crammed with figures from every walk of life up to their ears in every imaginable form of electoral flimflam and chicanery. Each of the four pictures focuses on a stage in the bitterly contested election and shows us the candidates doing whatever is necessary to win. Taken together they are a "progress" nonpareil.

Never completely confident that his "comic histories" could stand on their own two feet, Hogarth sought to endow them with timeless dignity by linking them to themes from the Renaissance and Baroque periods. The first, An Election Entertainment, was an elaborate parody of Leonardo's Last Supper, complete with the text: "He that dippeth his hand with me in the dish, the same shall betray me." Betrayal, along with drunkenness, violence, bribery and deception is, he shows us, the base coin of this appalling political banquet. In the second, Canvassing for Votes, he inverts The Choice of Hercules with a sly and knowing farmer who is 'allowing' himself to be bribed by two innkeepers, one from the Royal Oak (Tory) and another from the Crown (Whig). Choice is not necessary; both can be accomodated. The third, The Polling, borrows the theme of a platform from such works as Titan's Presentation of the Virgin; it ridicules the elaborate trickery by which the maimed and the dying are dragged to the polls and lawyers argue as to whether a man who has a hook for hand can "properly" swear on the bible. In the last picture, Chairing the Member, the disorder of the earlier scenes has erupted into open violence. Sending up Pietro da Cortona and Charles Le Brun's pictures of The Victory of Alexander over Darius, Hogarth replaces the imperial eagle that is said to have flown above the head of Alexander with a big, fat goose. The goose's inane cackling, it has been suggested, "will be the new member's contribution to parliamentary debate."

Hogarth's images frequently lend themselves to contradictory readings. Such is the case with Four Prints of an Election. On the one hand, it is impossible to doubt that he believed that factions had corrupted politics, that the electoral system was completely venal and that the common people could turn into a rabid mob at the drop of a hat. This, indeed, is what the Election prints show. On the other hand, he accepted the conventional notion that the English were "special" by virtue of their commitment to freedom and their hostility to authority. While these traits were, no doubt about it, virtues, they disposed the English, no doubt about it, to irresponsible, unpredictable, riotous behaviour. This, indeed, is what the Election prints show. It was Sam Ireland who remarked that it was "the madness" of elections that "proved the spirit of the people."